Public Health

Introduction

In the second half of the 19th Century parochial boards made up of landowners, kirk session and some elected members, had responsibility for dealing with public health. In addition to appointing an inspector of the poor who was in charge of the day-to-day administration of relief [Link to Welfare] they were responsible for regulation of lodging houses, removal of nuisances, construction of sewers, water supply and the control of infectious diseases. They were also given the power to appoint medical and sanitary inspectors and to deal with drainage and water supplies.

Parochial boards were replaced in 1894 by wholly elected parish councils and a Local Government Board for Scotland. Then in 1929 parish councils were abolished and their functions transferred to the county councils, district councils and town councils.

Medical Officers of Health

The 1889 Local Government (Scotland) Act made it compulsory for county councils to appoint county medical officers of health to oversee improvements in the health of the county. Duties of medical officers included the isolation and treatment of people suffering from infectious diseases and the identification of the source of such outbreaks.

Some larger rural communities, including Aberchirder, had become police burghs. The Police Commissioners – retitled in 1892 as councillors – took on a wide range of powers including public health. From 1897 they (and sanitary inspectors) were under the supervision of the Local Government Board for Scotland.

Dr Whitton was Medical Officer of Health for the burgh from 1893 until he resigned to become Provost in 1907. He was succeeded by Dr Moir who was not qualified in public health, and three years later Dr Ledingham, County Medical Officer, Banff was appointed.

Infectious diseases

The Town Council minutes record how infectious diseases were regularly reported by the Medical Officer of Health and Sanitary Inspector. In 1898, for example, there were cases of diphtheria (1), erysipelas (2), scarlet fever (2) and typhoid (1) Patients were removed to the Rose Innes Cottage Hospital’s isolation ward.

In the early 20th Century 1909 saw two cases of diphtheria, of whom one died in Rose Innes, the other being treated at home, while the MOH recommended the schools be closed for 10 days.

In 1914 there was a serious epidemic of diphtheria affecting school attendances and the area was affected by the Spanish flu pandemics of 1918 and 1919. During the 1920s there were epidemics of diphtheria, measles and flu, leading to school closures. And as late as 1932 six typhoid cases were removed to Campbell Hospital, Portsoy, with the Town Council burying one (shoemaker William Coutts) who died friendless and virtually penniless.

Public analyst

Under the terms of the Food & Drugs Act 1899 the Town Council appointed a public analyst in 1900 (£3 per year plus pay for work done), but by 1904 Banff County Council had taken over responsibility. One of the major jobs involved supervising dairies, with all of the 21 in the Burgh – with a total of 37 cows – to be registered in 1902. He also checked for adulteration of milk and butter as well as loose goods sold by grocers.

In the 1920s further controls were introduced under the Milk & Dairies Act – passed in 1914! – finally coming into operation in 1925. All dairies had to be registered and plans for milk houses to be approved. In late 1927 the Sanitary Inspector reported that several dairymen’s premises were not yet up to bylaw standard and they were given fourteen days to improve or they would be called before the Police Court

The slaughterhouse

One of the most important public health measures taken by the Town Council was the establishment of a burgh slaughterhouse. Before this butchers such as William Chalmers and John Sandison had their own slaughterhouses which had not been licensed and created a serious problem of pollution. In 1894 the County Sanitary Inspector complained that sewerage and rubbish from several dwelling houses and two slaughterhouses were polluting the stream that flowed through the garden and grounds of Auchintoul House and a ditch on part of Cornhill Road. The Town Council asked Mr Briggs, Burgh Surveyor of Banff, for advice and assistance and he submitted plans for a sewerage drain (costing £75) to solve the pollution problem and also for a new slaughterhouse (costing £185).

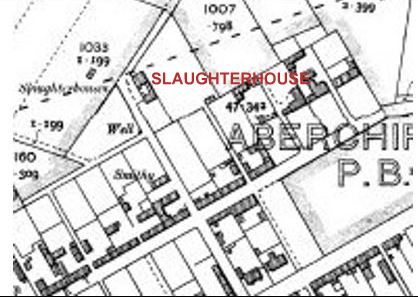

The Council decided to locate the slaughterhouse at the top of School Lane, which was at that time well away from houses. A feu charter was agreed with Provost George of Macduff, the landowner of most of Aberchirder, with feu duty set at £1.10s a year. The new facility was officially opened on 1 August 1895.

Location of burgh slaughterhouse at the top of School Lane.

Extract from OS map of 1904 reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the National Library of Scotland.

Sewage & Rubbish

Although there had been an extension of the fairly basic drainage system in 1883, sewage was a constant concern for the Council, which undertook a programme of building sewers along the main streets.

By the beginning of the 20th Century only a select few houses had installed WCs which, in view of the chronic water shortage, were not regarded favourably by the Council! These were connected to sewers which carried the waste to outfalls in South Street, from where open ditches ran to Arkland Burn.

The Rectory at the top of Main Street was too high to get pressure, so the Boyes family got water got from a street pump or well. Legend has it that when they had a new WC installed around 1900 the cistern had to be filled by hand and only the head of the household was allowed to use the WC while the rest (all ladies) had to use the outside privy!

Cesspools still existed in some gardens, causing a health hazard, and it is recorded that in 1900 the Town Council had to pay medical expenses for a young boy who had fallen into one!

As far as refuse was concerned, the Town Council in 1895 approached Alexander George, superior of the Burgh, and he “came last week and pointed out a place in the North-west corner [of Causewayend Quarry] that he is willing to give the Burgh for a rubbish depot”.